- Home

- Shoulder Anatomy

Anatomy Of The Shoulder

Written By: Chloe Wilson BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy

Reviewed By: SPE Medical Review Board

The anatomy of the shoulder makes it the most mobile joint in the entire body.

Just think about how much you can move your arm – you can reach forwards and back, up and down, across your body and behind your back, circle it round and twist it.

Functionally you can throw, lift, carry, push, pull, scratch your back, do your hair etc etc.

Shoulder anatomy makes all of this possible. The complex network of bones, joints, muscles, ligaments, bursa and cartilage are specially shaped and work together to make all this possible.

But all this mobility comes at a price. The shoulder may be the most mobile joint in the body, but it is also the least stable. And that can make it prone to injury.

Here we are going to look at the anatomy of the shoulder, what structures are involved, how they fit together and what can go wrong.

Shoulder Anatomy & Function

When we think about the anatomy of the shoulder, there are a few different parts:

- Shoulder Bone Anatomy: upper arm, shoulder blade and collar bones

- Shoulder Joint Anatomy: there are actually four different joints at the shoulder working together

- Shoulder Muscle Anatomy: a vast network of muscles surround and move the arm e.g. rotator cuff

- Shoulder Cartilage: special cushioning on your shoulder bones

- Joint Capsule: a bag-like structures that surrounds each joint

- Shoulder Ligaments: strong bands that connect the bones and increase stability

- Shoulder Bursa: small fluid filled sacs that provide cushioning and reduce friction

So let’s have a look at each of these features of anatomy of the shoulder and how they fit together.

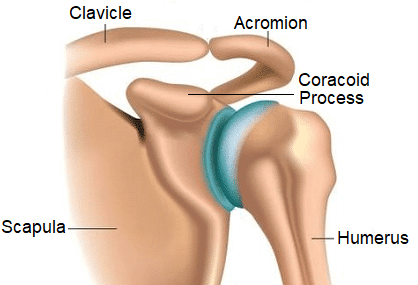

1. Shoulder Bone Anatomy

When looking at the anatomy of the shoulder, there are three main shoulder bones:

- Humerus: upper arm bone. The long bone that runs between your shoulder and elbow. At the top end is the humeral head, a hemispherical ball that forms part of the shoulder joint

- Scapula: shoulder blade. The scapula is a large, triangular bone that sits over the back of the rib cage. Two bony projections stick out the scapula, the acromion at the top and the coracoid process at the front.

- Clavicle: collar bone. The clavicle is the only long bone in the body that runs horizontally, sitting between the shoulder blade and the sternum (chest bone)

The shoulder bones connect our arms to our body and allow great freedom of movement in the upper limb.

The shoulder bones work like levers, transmitting the forces from muscle contractions to allow the arms to move.

Each of the bones is specially shaped to fit together to allow for the vast mobility at the shoulder.

You can find out more about the different bones associated with the shoulder, how they fit together and common problems that affect them in the shoulder bone anatomy section.

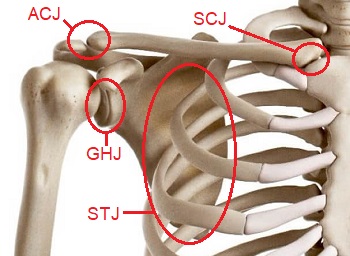

2. Shoulder Joint Anatomy

The anatomy of the shoulder comprises of four different joints:

- Glenohumeral Joint: the joint between the upper arm bone and the shoulder blade

- Acromioclavicular Joint: the joint between the shoulder blade and the collar bone

- Sternoclavicular Joint: the joint between the collar bone and the chest bone

- Scapulothoracic Joint: the joint between the shoulder blade and the rib cage

Collectively, these joints are known as the shoulder girdle. The anatomy of the shoulder girdle means that the joints actually work together to move the arm rather than in isolation.

For example, when you lift your arm out to the side, the following movements take place:

- Glenohumeral Joint: Abduction

- Scapulothoracic Joint: Lateral rotation

- Acromioclavicular Joint: Elevation and rotation

- Sternoclavicular Joint: Roll and slide and rotation

You can’t move one shoulder joint without moving the others. For example, try popping your hand behind your back and think about the movement that occurs at each joint – if it helps, pop your fingers over the joints one at a time and feel the movement.

You can find out all about the anatomy of the shoulder joints, how they fit together and work together and what can go wrong in the Shoulder Joint Anatomy section.

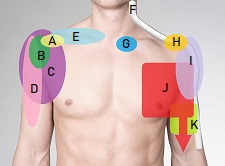

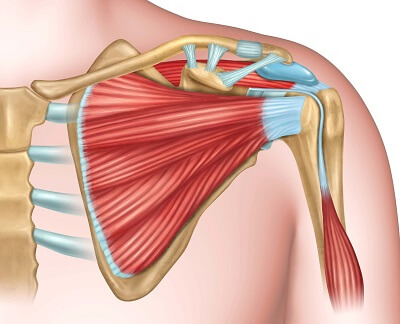

3. Shoulder Muscle Anatomy

There are around twenty muscles associated with the anatomy of the shoulder that work together to move and stabilise the shoulder. A great deal of stability at the shoulder comes from the muscles both at the shoulder and the shoulder blade. As the muscles contract and relax, they pull on the shoulder bones, causing the arm to move.

The main muscles in shoulder anatomy are:

- Rotator Cuff: a group of 4 muscles that run between the shoulder blade and the upper arm and are the prime stabilisers of the glenohumeral joint

- Scapular Stabilisers: a group of muscles that run between the shoulder blade and the spine and keep the scapula in the correct position

- Other Shoulder Muscles: such as deltoid, the pectorals and latissimus dorsi that move the arm in different directions

The shoulder muscles have to work hard not only to move the arm, but also to control it and keep it stable, otherwise there is a high risk of injury. This is particularly relevant when the arm is above head height or when carrying heavy loads.

Muscles injuries are common at the shoulder including:

- Supraspinatus Tendonitis: inflammation and wear and tear of one of the rotator cuff muscles

- Impingement Syndrome: irritation and damage to the muscle tendons

- Muscle Tears: over stretching or over loading the shoulder muscles can lead to tearing.

You can find out more about the anatomy of the shoulder muscles, how they work, what can go wrong and how to treat shoulder muscle injuries in the Muscles Of The Shoulder section.

4. Shoulder Cartilage

Cartilage is an important part of shoulder anatomy and there are two different types, articular cartilage and the labrum. The glenohumeral joint has both types of cartilage, the acromioclavicular joint and sternoclavicular joint have articular cartilage but the scapulothoracic joint has neither.

Articular Cartilage

Articular cartilage is a layer of tough, flexible connective tissue that lines and protects the ends of the shoulder bones. The cartilage covers the joint surfaces and acts as a shock absorber, allowing smooth, friction-free movement of the bones. Shoulder articular cartilage is approximately 1.2-1.5mm thick.

Shoulder articular cartilage injuries usually fall into two categories:

- Focal Injury: where a small area of cartilage is damaged, usually as a result of an injury such as a fall. Tends to affect young-middle aged people

- Wear and Tear: where there is gradual destruction of the cartilage over a larger area, usually from repetitive strain and friction which can lead to arthritis. Tends to affect people in middle-old age

Common symptoms of articular cartilage damage include shoulder pain, swelling, stiffness, clicking, catching or grinding sensations. Shoulder cartilage has a poor blood supply so is slow to heal after injuries, but rotator cuff strengthening and scapular stabilization exercises can really help.

Damage to the articular cartilage at the shoulder is often accompanied by other injuries such as impingement syndrome and joint dislocation.

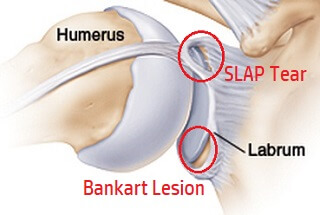

Glenoid Labrum

The glenoid labrum is a really important component in the anatomy of the shoulder. The shoulder labrum is a special ring of cartilage that runs round the edge of the shoulder socket (glenoid cavity) on the scapula. The shoulder labrum is approximately 4mm thick and helps to deepen the socket, increasing the stability of the glenohumeral joint.

Glenoid labrum tears may occur from a one of injury such as a fall or shoulder dislocation, or from gradual wear and tear.

There are two main types of glenoid labrum tear:

- SLAP Tear: a tear at the upper rim of the labrum, running from front to back

- Bankart Lesion: damage to the lower portion of the labrum

Glenoid labrum tears often present with a dull aching pain, weakness, instability, difficulty throwing and catching sensations in the shoulder region. They are often associated with other injuries such as joint capsule damage and shoulder fractures.

In most cases, glenoid labrum tears can be treated with rehab but in more severe cases, surgery may be required. You can find out all about the causes, symptoms and treatment options for shoulder labrum tears in the SLAP Tear and Bankart Lesion sections.

5. Shoulder Joint Capsule

Another feature in anatomy of the shoulder joint, apart from the scapulothoracic joint, is the joint capsule which envelops and surrounds the joint. Think of it like a bag tied around the joint that seals the joint. The joint capsule provides both passive and active stability to the shoulder joints.

There are two parts to the shoulder joint capsules:

- Outer Fibrous Membrane: attaches around the whole circumference of the joint, surrounding the entire articulation. The outer membrane is made up of dense connective tissue

- Inner Synovial Membrane: absorbs and secretes synovial fluid which lubricates and distributes nutrients to the joint which helps to both nourish the joint and provides some shock absorption

The glenohumeral joint capsule is fairly lax compared to the other shoulder joint capsules to allow for the large range of motion at the joint. Each of the shoulder joint capsules are supported by various ligaments to help increase joint stability.

Joint capsule injuries are common and may lead to laxity or constriction of the joint. The most common joint capsule injury at the shoulder is adhesive capsulitis, more commonly known as a frozen shoulder.

6. Shoulder Ligament Anatomy

The shoulder ligaments are thick, tough, flexible fibrous bands of connective tissue that link bone to bone. They help to reinforce and support the joint capsule and play an important role in joint stability.

The shoulder ligaments each get their names from the bones they attach to:

- Glenohumeral Ligaments: Three ligaments connecting the humerus to the glenoid cavity, the superior, middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments. They reinforce the joint capsule to increase stability at the glenohumeral joint. In fact, the glenohumeral ligaments are the main stabilising structures of the glenohumeral joint.

- Acromioclavicular Ligament: runs horizontally between the acromion on the scapula and the lateral end of the clavicle. There are two parts, the superior and inferior acromioclavicular ligaments that run over the top and bottom parts of the joint respectively. The acromioclavicular ligaments reinforce the joint capsule providing horizontal stability.

- Coracoclavicular Ligament: comprises of two ligaments, the conoid and trapezoid ligaments that run between the clavicle and the coracoid process of the scapula to help maintain the alignment between the collar bone and shoulder blade. The conoid and trapezoid ligaments are very small, but extremely strong.

- Coracohumeral Ligament: runs between the coracoid process at the front of the scapula and the greater tubercle just below the head of humerus. The coracohumeral ligament helps support the top part of the joint capsule to increase joint stability.

- Coracoacromial Ligament: runs between the acromion and coracoid processes of the scapula to form the coracoacromial arch over the glenohumeral joint, helping to provide stability and protection. Thickening of the coracoacromial ligament can cause impingement syndrome

- Costoclavicular Ligament: runs between the medial end of the clavicle and the first rib. It is the main stabilising structure of the sternoclavicular joint

- Sternoclavicular Ligaments: run between the medial end of the clavicle and the sternum, strengthening the joint capsule of the sternoclavicular joint. The anterior sternoclavicular ligament is found at the front of the joint, and the posterior sternoclavicular ligament at the back

- Interclavicular Ligament: a longer ligament that runs between the right and left clavicle, spanning the gap between the bones and reinforcing the sternoclavicular joint capsule at the top.

7. Shoulder Bursa Anatomy

Another feature in the anatomy of the shoulder is the shoulder bursa, small fluid-filled sacs that sit between muscles, tendons and bone to reduce friction and prevent wear and tear. There are approximately eight bursa located around the shoulder region.

The shoulder bursa provide cushioning and allow the soft tissues to move freely without any friction as you move your arm. However, they are prone to damage.

If there is too much friction or pressure through the shoulder bursa, they become inflamed and swollen, known as shoulder bursitis. This most often happens in response to repetitive friction from poor shoulder stability or abnormal shoulder anatomy but can also happen after an injury. The most common types of shoulder bursitis are subacromial bursitis (top front shoulder pain) and scapulothoracic bursitis (shoulder blade pain).

You can find out all about the different types of bursitis including the causes, symptoms and treatment options in the shoulder bursitis section.

Anatomy Of The Shoulder Summary

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body, controlled by the careful co-ordination of four separate joints that work together to allow for full shoulder range of motion. The main components of the anatomy of the shoulder are:

- Shoulder Bones: humerus, clavicle and scapula

- Shoulder Muscles: including the rotator cuff muscles

- Shoulder Ligaments: thick, flexible bands of connective tissue that link bone to bone for stability

- Joint Capsule: tough fibrous sleeve that surrounds the joints and nourishes them

- Glenoid Labrum: ring of cartilage that deepens the shoulder socket for increased stability

- Shoulder Bursa: fluid filled sacs that reduce friction between bones and soft tissues

- Cartilage: thick, fibrous tissue that lines the joint to protect the bones

- Hand Bones: 27 bones arranged in 3 groups, carpal, metacarpals and phalanges

The anatomy of the shoulder allows for a huge range of movement in multiple directions, but the lack of stability makes the shoulder prone to injury.

Related Articles

Shoulder Problems

January 29th, 2026

Shoulder Diagnosis

June 25th, 2025

Pain At Night

November 5th, 2024

Page Last Updated: December 10th, 2025

Next Review Due: December 10th, 2027